Summary

Last time, in The Goods Market, we discussed fiscal policy, such as how demand changes if increases by a certain amount. Today, we will talk about monetary policy. Unlike governments or people, the central bank cannot buy stuff, so it affects the economy more indirectly.

Example

In the US, there’s a Board of Governors with 7 governors appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate. Then, there are 12 regional banks, and the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), which is a board with 4 regional bank presidents.

Monetary policy is a lever for the short term. It is the prominent anti-cyclical aggregate demand policy, since fiscal policy is less flexible. In the longer term, it determines price level and inflation.

How does it act? Through financial markets, which are very complex. The central banks don’t participate in the markets but their actions affect prices. To simplify this exchange, we will assume investors only have the choice between money and bonds.

- Money is for transactions, but it pays no interest

- Bonds pay an interest rate but cannot be transacted with There is an inherent trade-off between the two, and we will study how the dynamics between the two shift (i.e. which share of wealth is in each asset class at a given time). At the level of the economy, we have:

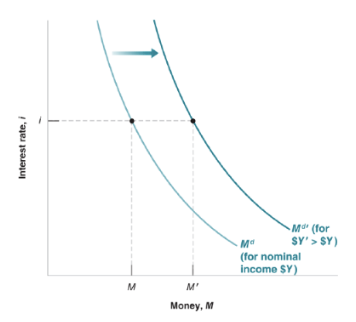

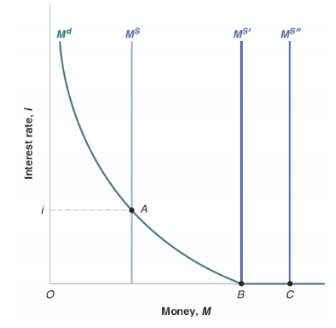

Remember that \ Yis [[Basic Macroeconomic Concepts#gross-domestic-product|nominal GDP]], whileL(i)$ is a function of the interest rate. The function is decreasing, since the demand for money decreases as interest rate increases.

Example

As nominal GDP increases, our chart shifts right.

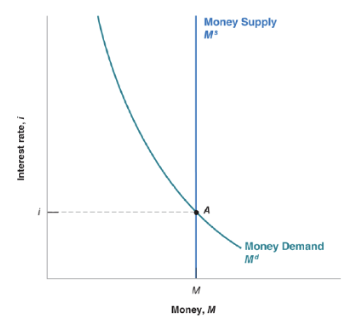

In equilibrium, money supply equals money demand, i.e.

Example

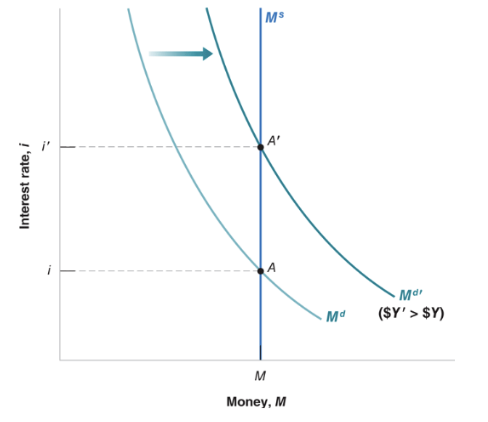

Notice that the central bank decides how much money is supplied, hence effectively deciding the equilibrium interest rate. However, money demand is unstable, so you cannot predict interest rate easily. Most central banks solve this by deciding the interest rate and then adjusting money supply accordingly.

Example

An increase in nominal income:

The Liquidity Trap

The zero lower bound is the idea that the interest rate cannot go below zero. The economy is in a liquidity trap when the interest rate is at zero, so expansionary monetary policy becomes null.

Open Market Operations

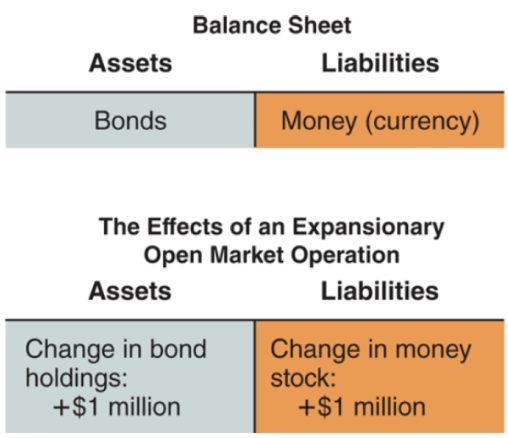

Open market operations are how central banks change the supply of money: they buy or sell bonds in the bond market, directly or indirectly. The idea of expansionary open market operation is when the central bank buys bonds, and contractionary represents the vice versa.

In essence, buying bonds issues more cash, which is why expansionary monetary policy pumps more money supply.

In essence, buying bonds issues more cash, which is why expansionary monetary policy pumps more money supply.

Example

Suppose a bond promises to pay $100 a year from now. If the price of the bond today is

\P_B$, then the interest rate is

The higher the price of the bond, the lower the interest rate. The higher the interest rate, the lower the price of the bond. When the central bank buys a bunch of bonds, the price goes up, so the interest rate goes down.

The Equilibrium Interest Rate with Intermediaries

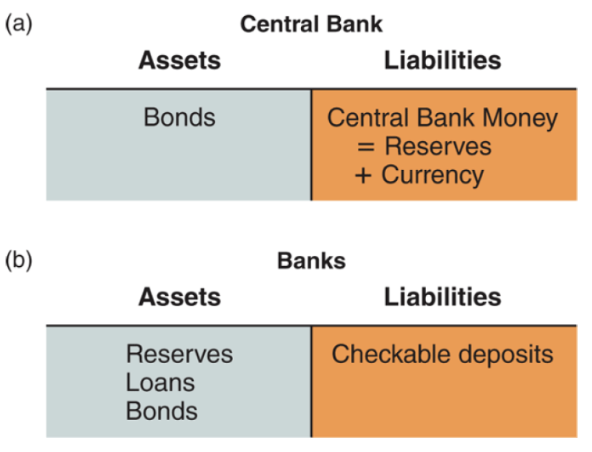

Financial intermediaries are institutions that take funds from people/firms and use them to buy financial assets and/or to make loans to other people. Banks are intermediaries that have money in the form of checkable deposits as their liabilities. These banks keep as reserves some of the funds they receive, and the liabilities are the money they issued, called central bank money.

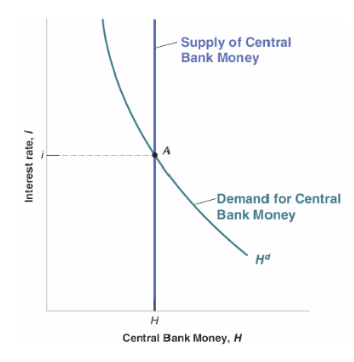

All these factors adjust the actual equilibrium interest rate, as illustrated below:

If people held no currency, the demand for money is the demand for checkable deposits:

If people held no currency, the demand for money is the demand for checkable deposits:

The demand for reserves by banks depends on the amount of checkable deposits:

where is the reserve ratio, and is the demand for central bank money, or the monetary base. Let be the supply of central bank money. Then, the equilibrium is

There is still no currency here, as everything is held in reserves.

The federal funds market is an actual market for bank reserves. The federal funds rate is the interest rate determined by the federal funds market, and the Fed controls it by changing .